Loung Ung…Surviving the Killing Fields of Cambodia

*Top photo: Fields in Loung Ung’s family village ~

Loung Ung lived through the Communist control of Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, lost family in the infamous “killing fields,” and was taught to be a child soldier. But her first major challenge in living in America was Independence Day, 1980.

“…And when the first fireworks went off, I tried desperately to crawl under the bed, screaming and crying,” she said about the Fourth of July celebration with her adoptive family. The young girl could not grasp why those around her did not fear the arrival of soldiers.

“…I would have become a very efficient killer, soldier, who would have killed, instead of a human rights activist.”

“I did not understand,” she recalled. “But for those that did not survive wars, the wars did not follow them.”

Loung Ung recently spoke at Unity Dallas as part of the Dallas Holocaust Museum’s Upstander Speaker Series, which brings renowned activists on human rights issues to the D/FW community. Ung has authored or coauthored books about her survival,including First They Killed My Father which became a film by the same name, directed by Angelina Jolie.

“My Cambodia was not unlike other people’s families,” she remarked on her household of nine, sharing how her brothers would listen to Elvis Presley and attempted to grow out their sideburns. “My Cambodia was filled with three sisters who I played with so loud and often my father threatened to replace us with monkeys.”

She described the nation as a green country the size of Oklahoma where 90% of the seven million citizens were farmers.

Ung said that there was nothing out of the ordinary about her family.

Her father attended school three times a week in Phnom Penh to study Cambodian, French, English, and Chinese. “My mother, who was at five-seven, was the Amazon in our society,” she joked.

She was five on April 17, 1975, when Communists came to power after U.S. forces left Southeast Asia, Pol Pot’s troops declaring that war was over and the country was finally going to be liberated.

“And when the soldiers came, they came in their slack shirts and pants, their guns at their knees, smiling huge smiles…” and evacuated Ung’s family, claiming the Americans were coming back to bomb the city.

That lie led to the family grabbing only what they could carry for a seven-day journey by vehicle and on foot to Krang Truop, and eventually to Ro Leap months later. It was there the family was separated, her brother Keav eventually dying in a work camp in 1976, and her father, a member of the pre-Communist military, taken away by soldiers and disappearing later that year.

“It didn’t matter if you were six or 60; you worked, and dug trenches, and grew food, of which the truck would come and take away, and return with missions and guns,” she said. Speaking out endangered individuals and their families. During Pot’s reign, an estimated two million Cambodians — approximately a quarter of the country’s population — were killed by violence, starvation or disease.

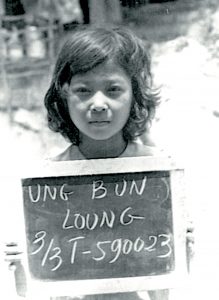

In 1977 when Ung was seven, she posed as an orphan at the urging of her mother and arrived at a camp where she was trained as a soldier.

“They put guns half my body size, a third my body’s weight [into my hands] and taught me to shoot and hurt and kill,” she confessed. “Is it that unimaginable, with that kind of training, that had the war not ended I would have become a very efficient killer, soldier, who would have killed, instead of a human rights activist?”

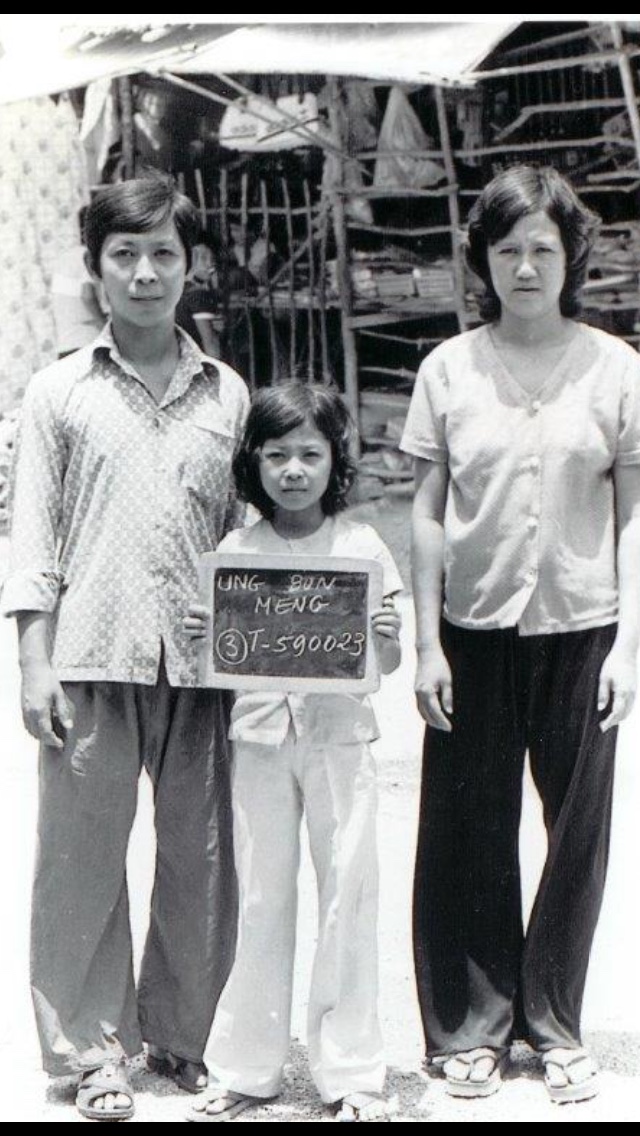

Crediting her mother’s strength, she and four siblings were able to walk out of the killing fields alive. As her surviving family members were splintered throughout Vietnamese-occupied Cambodia, Ung was smuggled into a Thai refugee camp. In 1980, at age 10, she moved to the U.S. to live with sponsors in Vermont, along with her older brother Meng and his wife.

“I didn’t speak English. I didn’t know anything about meatloaf,” she humorously recalled. In this land where things were “shiny and new” for her, her educational opportunities grew; not just academically, but in the world beyond Vermont or military encampments.

Still, war followed her. Unraveling her fear and anger took years.

She admitted that attempting to abandon her past life also meant letting go of some positives.

“Because in making myself forget the horrors, I also forgot the love. I forgot the courage; I forgot the light.” It wasn’t until the death of Pot in 1998 and viewing his last interview, as he rationalized his policies, that her anger shook her passions to the surface of her consciousness.

“A friend gave me a book that would save my life. The book is titled Man’s Search For Meaning by Viktor Frankl.” The wisdom the book revealed was her “greatest gift,” she expressed, “…to know that I was not alone in my pain and suffering… Mr. Frankl told me I was not broken.”

What drives Ung as an advocate for human rights is that what humanity once declared would happen “never again” continues to happen- in Rwanda, in Bosnia, to the Rohingya.

Even after the September 11, 2001 attacks, she maintained that there was a 50% jump in U.S. Cambodians seeking mental health counseling, which she attributed to the killing fields legacy, noting of a newer generation of Cambodians, “We had never seen war but if this place is not safe, where is?”

Ung described how she returned to Cambodia in 1995, reuniting with her surviving family and learning about the devastation antipersonnel mines from the nation’s past conflicts are still wreaking.

As the national spokesperson for the Campaign for a Landmine-Free World, Ung explained how land mines cost $3 to $5 to make but $1,000 or more to remove, disfiguring or killing 500 Cambodians a month even now.

“What we do matters,” she called from the stage, urging that upstanders do what is needed to create a safer, more just world. “What we do makes a difference. What we do [may] not change hearts and minds, but creates lasting change.”