If you have heard Judy Collins sing even once in the last 65 years — in person, on an album, or on your car radio — you know the power of her voice and how it can lull you and lead you. How it can make you smile or swoon or even shed a few tears.

We hear “Both Sides Now” and “Amazing Grace,” “Someday Soon” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” “Send in the Clowns” and “Since You Asked,” and her voice — that voice! — echoes in our heads and our hearts with the purity of a bell, of clear water over ice, of a yodel across the Alps, of an angel serenading only you. And as we listen to her sharing stories through lyrics that are often haunting and goosebump-inducing in their beauty, how can we not believe that all is right with the world?

Renaissance Woman

We never tire of Judy Collins, whose blue eyes are still brilliant, whose laugh comes easily, and who sounds like a schoolgirl. She is a jaw-dropping 84 now, and, to hear her talk, she is just getting started.

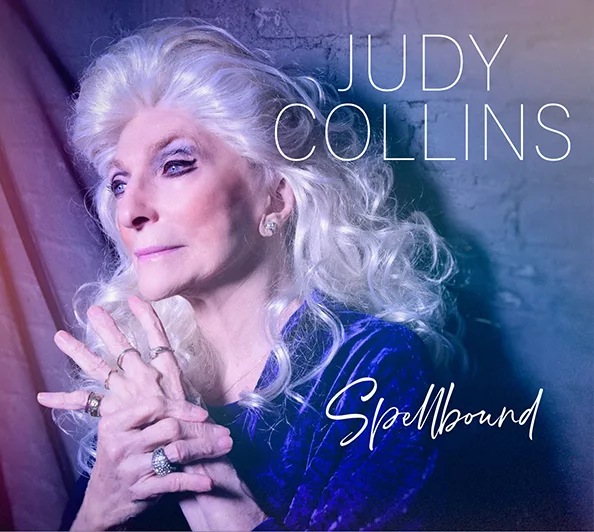

“Spellbound,” the latest of her 55-plus album repertoire and the first comprised solely of her own songs, came out in 2022 and was nominated for a Grammy Award.

“Spellbound,” the latest of her 55-plus album repertoire and the first comprised solely of her own songs, came out in 2022 and was nominated for a Grammy Award.

She paints watercolors. She stays in shape, and she continues to tour; on January 27, she’ll be at the Eisemann Center in Richardson performing with the Richardson Symphony Orchestra.

Recently, between performances in Great Britain and the Netherlands, she sounded surprised when even asked about not touring.

“Today I’m in Leeds, and it’s wonderful! Extraordinary!” says Collins, who grew up in Denver and continues to hold the mountains dear. (“When I Was a Girl in Colorado,” which is on “Spellbound,” is a poignant love letter to her home state).

“I love it here, and I’m having the best possible time. My band is marvelous,” Collins says. “No, no, I have no interest in stopping. I’m at the top of my game, and I’m having the time of my life. I’m the George Burns (a long-time performer who lived to be 100) of the folk movement, I guess.”

She’s thriving — creatively, artistically, musically, and physically.

“I have had a renaissance, no doubt about it. It’s all the work that’s gone on, and it’s also a very fortunate set of genes and a very fortunate lifestyle. I’ve been sober for more than 45 years, thanks to a 12-step program.”

She mentions her sobriety repeatedly, with an understood mix of pride, awe, and gratitude. The year she decided to tackle her dependence on drinking was 1977. She was dying, she says matter-of-factly; alcohol was killing her. So, not long after undergoing voice-saving surgery, which caused her to cancel 40 concerts and took her out of commission for more than a year, she went into a rehab program.

That saved her career. Most importantly, it saved her life, allowing her to thrive — thanks, she says, “to a whole host of other things that have come into play and involved physical health, mental health, determination, getting your ideas and your sense of where you’re going in life. I was also very lucky in the songs I chose and the people who chose to work with me and I with them.”

Looking Back on Judy’s Journey

Lucky. It’s a word she mentions often — talking about Louis Nelson, her husband of 27 years; talking about her granddaughter and great-grandchildren and her father, Charles Thomas Collins. He was himself a performer and hosted a radio show for 30 years.

“I watched him very closely from the time I was a little child, and I wanted to do what he did,” she says. “I wanted to sing. I wanted to play the piano. I was always practicing.”

A prodigy on the ivories, the piano was her first love and where she thought she’d make her mark. But she always sang — in the church choir, in the school choir, in the shower, at the dinner table. The eldest of five (four of whom are still living and remain very close), all the Collins kids could sing. The exception: “My sister,” Collins says, “who won’t sing. Or maybe she’s shy. Anyway, one professional singer in the family — well, two, Daddy and me — was enough.”

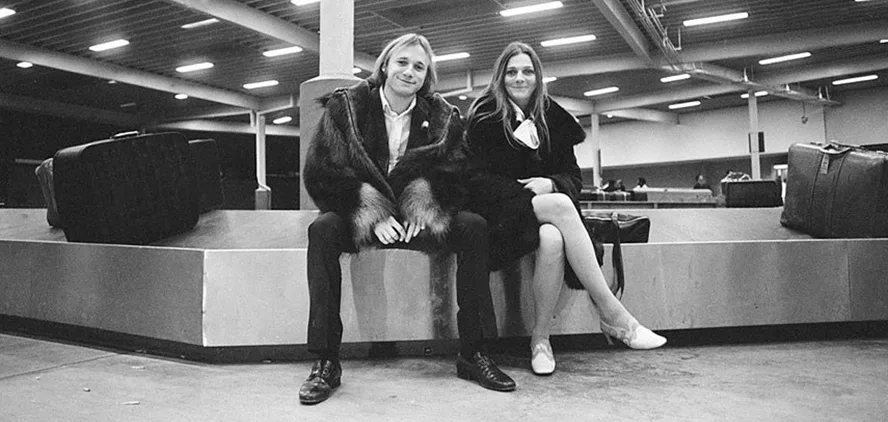

She considers herself lucky to have crossed paths and become close with the likes of (to name but a few) Joni Mitchell, Pete Seeger, Randy Newman, Stephen Sondheim, and, of course, Stephen Stills — who wrote “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” for her.

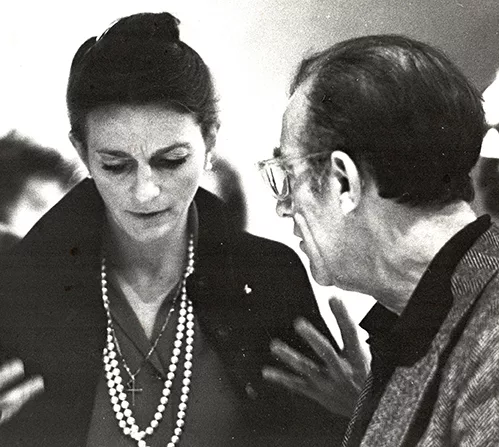

She was lucky, she says, to have studied under the greats, including famed musician and teacher Max Margulis. For 32 years, he helped train her voice in the Italian music style known as bel canto. Make your voice, he told her, “clear as a running stream, clean as a whistle.”

“Before he died,” she says, “I went to see him, and he said, ‘I don’t want you to worry. All you have to remember is phrasing and clarity.’ I know the reason I’m here doing this for all these years was because I listened to a man who could be impossible at times and his insistence on clarity and phrasing.”

Focusing on the Positives Today

Lucky comes up again when the conversation turns to the pandemic — one of only three periods in her life when she wasn’t performing. (The others were in 1962 when she had tuberculosis, and the bears-mentioning-again 1977).

“I’m thinking a lot these days at how lucky we are that scientists found a solution for COVID-19,” she says. “It took decades for the polio vaccine; people were dying all over the place. We’re so lucky to live in these times.”

Yet many of us lose sight of our blessings, she says.

“People lose sight of everything. They watch too much television. They’re on social media too much. I’m guilty of that sometimes, but I try to stay away from it. People don’t pray enough or go to church enough. They don’t sing enough or go to music concerts enough. They don’t go to museums enough. They don’t get out there enough and figure out what’s positive in this world.”

She continues to find plenty of positives, her health, for one. She keeps a Fitbit on her wrist to record her steps. She packs free weights for every trip out of town and runs around her hotel room when she has a few extra minutes. She wears an 8-pound weight vest to help strengthen her bones, gets regular massages, eats well, and takes vitamins to supplement her healthy diet.

Those habits help keep her ready for performing, which she calls “a privilege,” and which starts long before even setting foot on stage.

“You have to warm up and put on your makeup and your dress and be sharp and not eat dinner. Those aren’t routines; they’re ceremonies that help you focus yourself.”

She also says a prayer before every performance. And the minute she opens her mouth at her concerts, she says, she has a chance to get through to her audience — and herself. It’s a time to hone in on her own consciousness, just as she believes every audience member is doing within themselves.

“When they’re there, they can’t get on the phone,” Collins says. “They can’t talk to their neighbors. They have to think in the quiet and in the beauty of these songs.”

“As an audience, our subconscious is absorbing something that’s helpful and beautiful and timeless, and it connects us with everybody else who’s ever been on this planet. I think everyone is rearranging their ideas about the world in their silence, latching onto their sense of justice and purity, and deciding to live a life of joy and good acts.”

Every song ever written, her friend Yoko Ono once told her, knows where it is supposed to go. After years of singing her own songs and those of other artists, Collins has a pretty good sense of direction — tailoring the order of songs sung and stories shared to who is sitting in front of her on any given night. Turning them, as she says, “upside down, backward, and forwards. I keep it all real.”

There’s poetry to this — to her life and her words and, of course, to that incredible voice. Yet everyone’s life has its own poetry as well, one each of us needs to unearth, she believes.

“Everyone should write poetry, just like everyone should journal,” Collins says. She has kept a journal for as long as she can remember; many of them are now in the Library of Congress.

About those earliest journals — would Judy Collins today recognize the girl who wrote in their pages? And were she to have a conversation with that girl, what would she like her to know?

“All her misgivings and fears — I’d try to relieve her of those,” Collins says. “She’s better off not being terrified, I’d say. And I’d try to tell her every day how lucky she was.”