GARY LEE PRICE: Sculpting Spirit into Bronze Statues

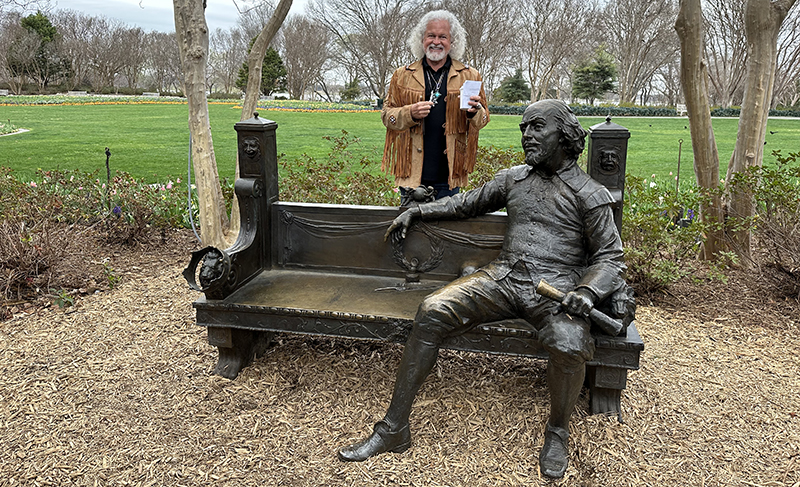

Gary Lee Price wants you to sit a spell. To take a load off your feet. To sidle up on bronze benches with people whose names you know but whose personalities you don’t. To share with them silence or small talk, deep thoughts, or random musings.

And, finally, with maybe a little reluctance, to walk away feeling closer than ever to his nine seated sculptures at the Dallas Arboretum.

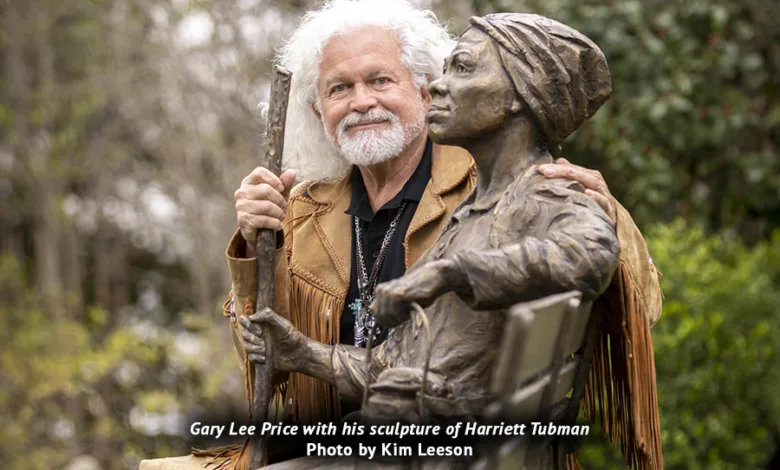

William Shakespeare is a full-time resident, having been purchased after an exhibit there four years ago. The latest eight bronzed historical figures, on view through Aug. 6, 2023, include Ruby Bridges, Amelia Earhart, Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin, Joan of Arc, Mother Teresa, Harriet Tubman, and Mark Twain.

They’re a mere sampling of the thousands of Price’s sculptures on display in parks, museums, institutions, exhibits, and homes across the world. Look at each of them and you see not only the talent of his hands, but also the outpourings of his heart

The Reasoning Behind the Bronze Benches

“I’ve always been inspired by others,” Price said, “and, by the same token, I thought we always put these people on pedestals. But guess what I found doing research? They all have faults. They all did stuff in which they compromised themselves.”

So, he removed them from their pedestal legacy.

“Let me bring them down to earth,” he said, “and put them on a bench. Let me go sit with them or meditate next to them and realize each was a real person.”

Price’s Process

Learning about everyone he decides to bring to life involves “massive research.”

“It’s watching every video, pulling up every documentary, reading anything I can get my hands on,” Price said of his method.

“I get 1,000 percent into that person’s character. When you’re sculpting three-dimensionally, it’s not like doing a painting and getting a quick blink of that person. It’s bringing out their character, their soul.”

He continued: “If I can capture that by learning who they really were, mission accomplished.”

And once he knows who they were, he further brings them to life — always using live models, including, quite frequently, his beloved wife, Leesa Clark Price.

If the sculptor’s eyes exude kindness and its demeanor a welcoming gentleness, he attributes those to her.

“Those kind eyes are energy,” Price said. “Everything exudes energy. If I can help people feel it and be touched by it, even in an inanimate piece of metal, that’s magic.”

For each subject, he focuses on individual gestures and on positions in which they seem at home.

With Mother Teresa, he asked himself, “What does she represent? God, and everything you wonder about that.”

He put the sainted nun, who wasn’t quite five feet tall, in a humble position, her radiant countenance gazing upward. He not only captured her spirit, but also her feet. Misshapen and deformed, they were a testament to sacrificed comfort, to wearing donated shoes that were often too small so others in need could wear the better-fitting pairs.

“I thought her feet were beautiful,” Price said. “They were part of who she was.”

Every sculpture begins as “a teeny tiny two-inch clay study. There’s no detail, just a shape,” he said. “Then I make a teeny bench. Then I go to a six-inch study with a little more detail, then 20-inch, and then life-size.”

After that, he drives it from his home in Arizona to Utah, where his foundry and mold makers are.

“It’s done the same way jewelry is cast,” he said, “only on a much larger scale.”

Each bench, for instance, weighs 500 to 800 pounds and is made of 30 pieces of solid bronze.

“People have no idea how many hours of very skilled workers it takes to do each of these,” he said. “It has to be perfect.”

A Cathartic Path Toward Sculpting

Price didn’t begin as a sculptor. Initially, he dreamed of becoming a portrait painter.

He had always loved to draw. As a little boy, his beloved mother, Betty Jo, encouraged his talent. But when he was six years old, living in Germany with his family, a incomprehensible tragedy befell him: His stepfather killed his mother, then himself. Price witnessed everything.

His love for drawing could easily have died there, as well. Instead, it was intensified by his first-grade teacher, Mrs. Anderson, whose class he was put into after returning to the U.S. to live with his mom’s first husband.

“She would hold up what I’d drawn and say, ‘Look what Gary Price did!’ That was a huge catalyst in my development,” he said.

“She had found out my parents had been killed and that’s why I was flown back to America. Her mindset was, ‘I’m going to get his mind on the positive after all he’s been through.’”

That focus has carried him and sustained him.

The bottom line, he said, is this: “That horrible event helped me become a sensitive, empathetic human being. I think anybody who goes through a massive trauma, a tragedy — if they’re somehow able to deal with it, to not deny it, to not go on some crazy aberrant behavior – becomes more sensitive.”

Price continued: “I feel what other people are feeling; I can see into their soul, their eyes. I attribute that to the tragedy and what happened there that night.”

At one point, he underwent hypnotherapy to help come to terms with what he witnessed.

But art, he said, “has been my savior. Writing my book (Divine Turbulence: Navigating the Amorphous Winds of Life) was very cathartic.

There is something very healing and magical in art therapy, in our heads and out on paper.” And in clay, which he didn’t discover until his last year of college at the University of Utah.

“I call what happened divine orchestration,” said Price, a former Mormon who continues to hold the religion in high regard.

“I had stopped by the studio of Stan Johnson, the sculptor, just to say ‘hi,’ and he asked me to work with him.”

Price said yes. After completing an already-scheduled trip to Guatemala, he trained for nine months with Johnson.

“I slept in his studio at night because I was a poor college student,” he said.

“At night, I’d sculpt on my own pieces, and bam! That got me on my way.”

He sold a few sculptures and, he said, “trajected upward, upward, upward.”

Next Project — The Statue of Responsibility

Price’s trajectory continues literally as well as figuratively as he embarks on his latest project: The Statue of Responsibility. If all goes according to plan, it could tower 350 feet into the west coast sky.

The sculpture is a dream of Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl. The late Austrian psychiatrist and author envisioned it as a West Coast companion to the Statue of Liberty — a tangible reminder that with freedom comes great responsibility.

Price came up with an idea: Two clasped hands, one reaching up and one reaching down.

“I sculpted it with the thought of all the people who had reached up and helped me, all those who have assisted me on my journey,” he said. “I wanted to depict that we can rise above any tribulations when people help us.”

In 2004, Price flew to Vienna to show it to Frankl’s widow, Elly, who loved it.

“It was like the choirs of heaven,” he said. “We got emotional; we hugged each other, and it was just amazing.”

His wife Leesa established The Statue of Responsibility Foundation, which is now looking for a place to construct the statue and as well as raise funding for the multimillion-dollar project.

“It’s finding like-minded people and institutions which get the vision of what this represents,” he said. “Responsibility means something — whether to humanity or to the planet, it’s a beautiful word.”

Meanwhile, he keeps learning about people, birds, animals, nature, and sculpting. If he needs to just pause and think, he can choose one of the thousands of benches around the world or in his own back yard in which to do so: To sit with one of hundreds of companions whose company he’ll always cherish.

On a recent trip to the Dallas Arboretum to promote his newest exhibit, Price made a point of spending time with his sculpture of William Shakespeare.

“While I’m sitting there looking at it, all these kids are coming up and sitting on him,” Price said. “They’re interacting with William Shakespeare. And, my gosh, the patina has worn off because they rub his head and sit on his lap.”

That, he said, “is the greatest compliment a sculptor could receive.”