A Teacher’s Bold Lesson on the Power of Literature

Why reading and engagement matter

When I taught, getting students to read—really read—was one of my biggest challenges. Nowadays, convincing kids to open a book feels like an uphill battle. Yet, the essence of teaching is to inspire engagement, just as the heart of learning lies in students’ willingness to engage. That paradox—where one cannot occur without the other—still lingers with me.

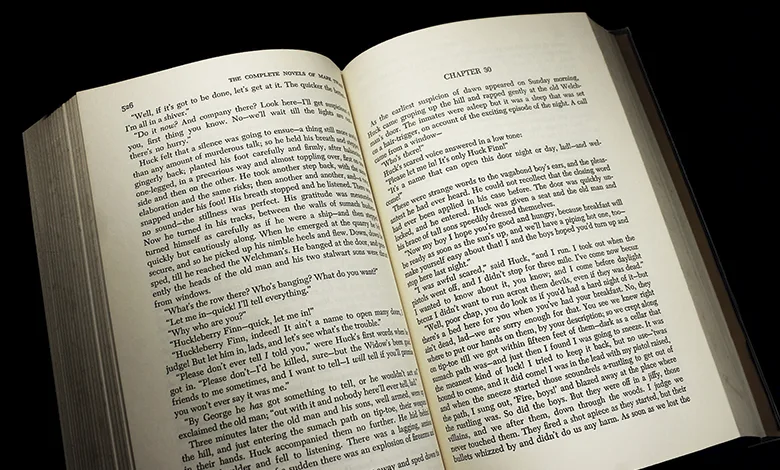

The debate over what students should read to sustain our cultural momentum continues. I can justify Hawthorne, Twain, Steinbeck, and Fitzgerald as the quintessential links from the past to the present. Still, even if we assign these authors, many students will wait for the movie or skip it entirely.

Words on a page exist in black and white, demanding a reader’s response. That response requires a willingness to engage and meet the writer halfway. But today’s students, often isolated by their AirPods and drawn to the instant gratification of streaming services, struggle with that level of commitment. Reading literature requires effort. It’s not passive entertainment; it asks for thought, imagination, and participation from the reader.

Over the years, I have tried cajoling, bribing, and coaxing my students to read. Sometimes, it worked. I discovered that great books—the ones that shadow you daily, lending their voice to your unique experiences—leave a lasting impression. Some books, however, don’t resonate as deeply.

One day, after teaching Hemingway’s “Farewell to Arms” for what felt like the hundredth time, I decided it was time for a dramatic farewell of my own. I met my class outside, butane torch in hand. “How many of you truly put your heart and soul into reading this book?” I asked. As expected, not many hands went up. “Over the years, you haven’t been the first to question why we read this ‘old stuff.’ But no one has ever asked me if I like teaching it.”

I held up the battered, dog-eared book. “Sometimes, not so much. At least, not with Hemingway. Any writer who has a female character say to a man, ‘You are my religion. I’ll do anything you want,’ or who has a macho male call his war buddies ‘a dog in heat,’ should stay dead. My humble opinion, of course.”

And with that, I donned goggles, lit the torch, and sent Hemingway’s novel to its final resting place. It was a cathartic, purging moment; Hemingway never believed in an afterlife.

But after my moment of insanity passed, I reflected on the lasting impression writers are supposed to have on readers. Ironically, my students will probably remember the day their crazed English teacher burned a book more than they will Hemingway’s quest to write one true sentence. For the record, I do not recommend burning books. In hindsight, that act was more of a theatrical outburst born of fatigue and frustration than a thoughtful statement and something that never happened again. But I hope my students took away something more profound: rejection is a sign of engagement.

To critique something honestly, you must first engage with it. That’s why I want students and adults to respond to books, even if their responses are negative. If someone reads Hemingway and says, “He stinks when he writes…,” they’ve engaged, thought, and evaluated. That kind of interaction keeps our cultural momentum alive. What dims our nation’s light is apathy—the blank stare of someone who hasn’t even read the title page.

Some books are powerful enough to transcend their covers, weaving into the fabric of our lives. But that can only happen when people actually read them. We need to read, think, and evaluate ideas in the natural habitat of the written word to maintain the intellectual momentum that defines us as a people.

So, it’s OK to say farewell to Hemingway—if you’ve read him. What’s not OK is the collective shrug that accepts influences that negate our need to engage critically with the written word. The future of our culture and our identity as a people depend on it.